Bob Howells

Writer and Editor

MASTER COLLABORATOR Ventura Blvd

There’s no pigeonholing The Soraya. Classical? Sure. Chamber? Of course. Jazz? Lots of it. Dance? Twyla Tharp’s troupe is on the way. So is Ballet Folklórico de México. Big philharmonic orchestras, intimate evenings with singers and instrumentalists, a mariachi opera, a trilogy honoring endangered California trees, a virtuoso mandolin player rocking Vivaldi. Performances in Spanish. Performances in English. Performances that transcend language. If you’re looking for a common thread to characterize the docket at the Valley’s premier performing arts center—well, good luck with that.

It’s tempting to say that the eclectic range of events at The Soraya reflects the broad tastes and experience of its executive/artistic director, Thor Steingraber. That’s probably true. But Thor himself would sidestep that and point to the Valley itself to explain the diversity of the arts on display in the 1,700-seat venue on the campus of Cal State Northridge.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE

A LEAGUE OF OUR OWN Westways

I was surprised to see Santa Claus at a ball game last summer. It was a 102-degree July day in San Bernardino, and as I settled into my seat before a game between the home-team Inland Empire 66ers and the Rancho Cucamonga Quakes, the jolly fellow ambled down the aisle—hot dog and drink in hand.

When “Winter Wonderland” blared over the sound system and a troupe of elves commenced dancing atop both dugouts, I figured something was up. “It’s Christmas in July,” the fan seated next to me explained. “You wear your Christmas PJs, you get in free.” If only I’d known.

In Minor League Baseball (MiLB), the sideshows sometimes overshadow events on the field. But if you love baseball like I do, like to sit close to the action, and enjoy a smidgen of frivolity for your less-than-$40 ticket, a minor-league game is the best show in town.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE

CHARLES FOX WROTE THE SONGS YOU'VE BEEN HUMMING ALL YOUR LIFE Ventura Blvd

What if I told you that the same composer who gave us the eternally catchy theme song to Happy Days back in 1974 also wrote and conducted, 35 years later, a moving oratorio called Lament and Prayer for the Poland National Opera Company? And that the same man who penned the themes for Love Boat and Love American Style has written three orchestral suites for internationally renowned ballet companies?

What if I told you the same man who wrote the Grammy Award-winning song “Killing Me Softly With His Song,” popularized by Roberta Flack in 1973, also wrote the Jim Croce hit “I Got a Name”? And listen up, sports fans—this same guy also wrote the stirring theme for ABC’s Wide World of Sports. (You know: “The thrill of victory, the agony of defeat.”) And soon after, the theme for Monday Night Football.

All of this is on top of dozens of film scores, numerous other TV themes and other concert works. The same man wrote them all.

The man is Charles Fox, who is 83, lives in Encino, and the fact that he’s still active, still composing and still performing shouldn’t by now surprise you.

HANDWRITING ON THE WALL Fore Magazine

Gather ’round, golfers and fans, and hear tell a tale of yore, a distant past before tournament scores were rendered scrollable on your phone, and before digital scoreboards the size of drive-in movie screens blared results visible from a long-iron shot away. We’re talking about the antiquated art of pen on paper. But not just any pen or any paper. We’re talking calligraphy. Leaderboards rendered as lovingly as love letters, by artists directly descended from Belgian monks who spent lifetimes illuminating sacred manuscripts, and whose latter-day cousins hand-post runs, hits, and errors on Fenway Park’s Green Monster.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE

AN HOMAGE TO OUR NATIVE OAK TREES Ventura Blvd

California oak trees live in my heart and soul. I miss them when I travel, and they signify “home” when I return. They dazzle me, enchant me, and make me think I’m a photographer, because simply aiming a camera in their general direction yields a masterpiece every time. (Which is why my phone is full of “oak porn.”) How often do I stop the car to admire a magnificent oak tree? More than my wife cares to count.

Happily, opportunities to pull over and go gaga over an oak tree are ubiquitous all up and down the hills and valleys of California west of the Sierra. Every other street or development carries some version of “oak” in its name. Heck, the very word “Encino” is Spanish for oak. “Thousand Oaks” is English for “probably more like a million oaks.” Oak trees line our streets, cluster along our hiking trails, shade our parks—and they are so beautiful.

PRODUCED BY Copy Editor

Produced By, published by the Producers Guild of America, is one of several magazines for which I serve as copy editor.

DEATH VALLEY FOODIE HAVEN Los Angeles Times

LOS ANGELES TIMES

By any drive-by or drive-through impression, Tecopa looks bleak. The small desert town on the stoop of Death Valley has a smattering of trailer homes, a couple of time-warp motels and some hot springs. Barren mountains form its backdrop. No gas stations. No stores.

I had driven by Tecopa many times and through it twice (it’s an eight-mile detour off California 127 on the way to Death Valley National Park, whose boundary is 10 miles north), and my salient impression was, “Man, this place is strange.” Then I heard something that sounded unlikely: Tecopa, 230 miles northeast of Los Angeles, was becoming some sort of foodie haven. I didn’t realize there were places to eat in Tecopa. Not only that but two microbreweries had sprung up.

The rumors are true. Tecopa not only has great food and brews but it also harbors places of genuine beauty, and its hot springs are salubrious. As for accommodations, if you don’t expect too much, you might be pleasantly surprised.

THE COSTUME DESIGNER Copy Editor

The Costume Designer, published by the Costume Designers Guild, is one of several publications for which I serve as copy editor.

PRAIRIE HOME National Geographic Traveler

I’ve been writing for magazines for a long time, but to score a 14-page feature in the June/July 2019 issue of National Geographic Traveler was pretty special.

At the end, the author bio note reads: “Robert Earle Howells is a California-based writer whose passion is public lands that preserve disappearing landscapes.”

This feature is special to me for that reason, and others as well. This was my third visit to the prairie over the course of 30 years, dating back to a trip I took when I first started freelancing. That trip was all about, yep, public lands—and proposed public lands—that preserve disappearing landscapes.

Also special is the fact that my host in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, on all three trips was Harvey Payne, and several of his photographs are included in the feature. There’s also a gorgeous sunset shot by my buddy Matt Payne (no relation to Harvey). The three of us spent one long day and evening out on the prairie together. Very special.

READ THE STORY

SHOULD WE HIDE THE EARTH'S GREATEST TREES? SF Chronicle

This piece for the San Francisco Chronicle won a Lowell Thomas Award from the Society of American Travel Writers Foundation and was honored by the North American Travel Journalists Association as one of the best newspaper travel stories of 2018:

An excerpt:

Redwood trees are giant collective spirits — ecosystems, in the scientific parlance. Why single out one, when the collective has such profound presence and significance? It’s how those trees interact with one another and with their understory that enables them to reach such magnificent heights. That’s the source of their majesty. Not a cool name or a world record.

I would encourage anyone to make the Tall Trees hike, and discourage anyone from attempting to reach Hyperion. Some locations, some trees, should remain secret, untrammeled, and probably unnamed. Let them flourish in anonymous silence. Let us look out from afar and be happy that they’re there, and proud that 50 years ago we established a national park to protect them.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE

COPY EDITOR The Golden State Company

As I like to say, I’m the rare writer who’s a good editor, and the rare editor who’s a good copy editor. It all stems from my love of language and a penchant for getting the details right.

As copy editor for The Golden State Company, I edit two print magazines: Ventura Blvd, the city magazine for LA’s San Fernando Valley; and Produced By, the trade magazine for the Producers Guild of America.

Let me know if you find any typos.

UNITED STATES OF ADVENTURE Outside Online Content Marketing

The marketing arm of Outside magazine taps me for big projects like this one: an interactive guide to overlooked parks and recreation areas in all 50 states. I wrote all of the western states and a few others for this superbly produced guide.

By the way, states like Nebraska and Kansas get equal billing with the Oregons and Californias of the world. A bit of a challenge that I relished. To wit...

Excerpt:

Nebraska recently had some fun with a jokey tourism tagline: “Nebraska. Honestly, it’s not for everyone.” That’s partly true because no place is for everyone and partly because, out of the city limits, there's hardly anyone around. Either way, Nebraska upends the old notion of endless cornfields by serving up genuine beauty spots, majestic rivers like the Niobrara and the Platte, and even pine-covered mountains. The prevailing terrain is the Great Plains, but the landscape gets broken up by dramatic geological features like badlands and bluffs, and some good old-fashioned lakes and streams where you can simply lollygag. Unless, of course, the walleye are biting.

VIEW THE INTERACTIVE GUIDE

CALLED TO THE WILD National Geographic Traveler

My love for the outdoors extends naturally to a love for encountering wildlife in their natural habitat. This feature for National Geographic Traveler won the Travelers’ Tales Solas Award for Best Adventure Travel Story. It was also cited by the judges when I was named the Lowell Thomas Silver Travel Journalist of the Year.

“Bob Howells does not just write about nature—he becomes one with it. In fact, if you are not careful, you will find yourself transported into a remote and vast landscape or seascape. And he knows just how to hook you along. In ‘Called to the Wild,’ written for National Geographic Traveler, Howells does just that.”

Excerpt:

How I came to be snorkeling in Hudson Bay not far from 3,000-pound beluga whales is the story of a growing obsession. Over the past few years, I’ve watched humpback whales feed off the British Columbia coast, hovered offshore in a kayak while grizzly bears munched on tender late-spring grass, cast a flashlight beam on skulking caimans (crocodile cousins) from a canoe in the Amazon, watched elk rut on a Banff golf course, and tiptoed through a herd of wild bison on an Oklahoma prairie.

In a world teeming with virtual adventures, encountering wildlife in their natural settings is a refreshing dose of reality. Increasingly, it’s what I seek in my travels. When I can hear the splashing crescendo of a whale’s breach, smell the pungent muskiness of a herd of elk, or catch the glint of a gator’s eye, I know that a bit of the real world endures. I like being reminded that separation from the natural world is an illusion. Indeed, here I am, as alive and breathing as the creatures I’m watching.

Or the creatures watching me.

READ THE FEATURE (Download pdf)

NO FEAR OF FLYING Golden State

As the son of an Air Force pilot, I’ve always loved aviation, and I’ve had a crazy bunch of aviation experiences, from taking the wheel of a Cessna at age 5 to going zero gravity to pulling 5g’s with an aerobatics pilot. All of that positioned me to be the right guy to profile Peter Jones, writer/director of a four-part history of SoCal aviation. It ran on the Golden State website, in Ventura Blvd, and in Southbay.

Excerpt:

Very early in Blue Sky Metropolis, Peter Jones’s four-part documentary on the history of aviation in Southern California, we see an old film clip of a propeller-driven dirigible attempting to take off during the 1910 Los Angeles International Air Meet in Dominguez Hills. It looks utterly preposterous. No one watching—then or now—could hold any hope of it getting airborne. But fly it does, as a nattily attired and apparently untethered pilot steers from an exposed framework underneath the behemoth airship.

The image says a great deal. It speaks to the audacity of early aviation pioneers, those magnificent men and women in their flying machines. It speaks to the power of dreams and to the can-do spirit of a collection of dreamers. And more specifically, it establishes Los Angeles—and all of Southern California—as the cynosure of a nascent movement to reach the sky, the heavens and beyond. The dreams and the dreamers belonged uniquely to Southern California.

READ THE STORY

RUNNING POINT CAPITAL ADVISORS Copywriting

Running Point is a Moon Tide Agency client that offers a unique, team-oriented approach to wealth management. They serve their high-net-worth clients with a full range of services—investments, tax planning, estates, trusts, insurance—all under one roof.

To amplify the team approach, I suggested a visual series in the header that illustrates the importance of teamwork, with this copy: It takes a team... to realize dreams... to accomplish goals... and secure the future.

I also wrote all of the copy on this very deep website.

JUST AHEAD Smartphone Audio Guides

Just Ahead smartphone audio guides play as you drive through national parks or along scenic highways, giving you a GPS-triggered tour of exactly what you’re seeing outside your car window.

I worked with Just Ahead founder/CEO Gregory Morse from the outset in developing these guides, which are truly technological marvels. They work seamlessly to deliver professionally narrated content, including back stories, history, natural history, and useful driving directions.

I have written about a dozen of the guides, and hired freelancers to write a bunch more, which I edited and produced.

I also write Just Ahead’s blog posts, trip-planning guides, web copy, and promotional materials.

CHECK OUT JUST AHEAD

AT HOME ON THE RANGE National Geographic Traveler

I’m particularly proud of this feature about Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota: nine colorful pages plus jump copy. For one, the assignment was initiated by the late Keith Bellows, one of the finest print editors ever, as the magazine’s homage to the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service.

It also gave me the chance to commune with one of my conservationist heroes, Theodore Roosevelt, in a setting that was deeply meaningful to him.

This article won the Gold Award from the Society of American Travel Writers Western Chapter for Best Article on US Travel.

Excerpt:

I OWN a prairie dog colony in North Dakota. Not that its residents are impressed with me at the moment. The trail I’m walking bisects their turf, and they’ve come out in force to scold me for the intrusion. My prairie dog town is in the 70,000-acre Theodore Roosevelt National Park, which is mine too, as are the granite walls of El Capitan in California’s Yosemite National Park, the lakes of Michigan’s Isle Royale National Park, and the stalactites and stalagmites of Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave National Park. Simply by being an American, I hold collective title to these and other profoundly beautiful places—an inventory that is the envy of the world—thanks to the establishment of the National Park Service a century ago.

Just beyond my prairie dog colony, a movement, something large, catches my eye. Bison? Bighorn sheep? I veer off-trail and spot four mustangs grazing near a copse of junipers. As I edge toward them, they warily edge away. Then one prances and the others follow, inscribing an arc around me.

Then it strikes me: What could be more fun, more free, than to be a mustang with thousands of acres of grassland to roam?

READ THE ARTICLE (PDF Download)

THE TEACHINGS OF MOISES CHAVEZ Outside Magazine

The Teachings of Gerineldo Moises Chavez, or, The Rainforest Is a Great Place to Save, But I Wouldn’t Want to Live There

This experience of jungle survival in the Amazon Basin predated all those ensuing reality shows about weird survival experiences. This one was tough—and real—enough. A week in the Amazon, living off the land. What did I take with me? A machete, a toothbrush, and water purification. And a great photographer, Bill Hatcher, who endured all the same deprivation as I did.

Worth it? Well, I fell in love with the jungle and with birds. And our guide, Moises Chavez, is an extraordinary character. But Bill and I agreed that if we had it to do over, we’d cheat.

This article won a Lowell Thomas Gold Award for Best Adventure Travel story. I also went back to the Amazon to film the experience for Outside Television, which I wrote, narrated, and was featured in. The lower two shots at right are screen grabs from the film.

Excerpt:

“We have only grubs to eat,” Moises said, sounding somewhat apologetic.

“Great,” I replied, in all earnestness.

I’d had it with hunger. I'd had it with wet. My own scent offended me. My arms ached from waving off kamikaze flotillas of mindless, DEET-disrespecting mosquitoes. I’d had it with sweat bees, desperately in love with my sodden leather boots, clouds of them swirling around my feet at every stride. I was a starved sweat machine, a giant itch, a pathetic, sleep-deprived gringo who couldn’t even catch an agouti for dinner. But at least I’d developed a yen for grubs. When you’re trying to live off the land in the green heart of Peru's upper Amazon rainforest, strange things begin to happen.

You learn to like beetle larva.

READ THE ARTICLE

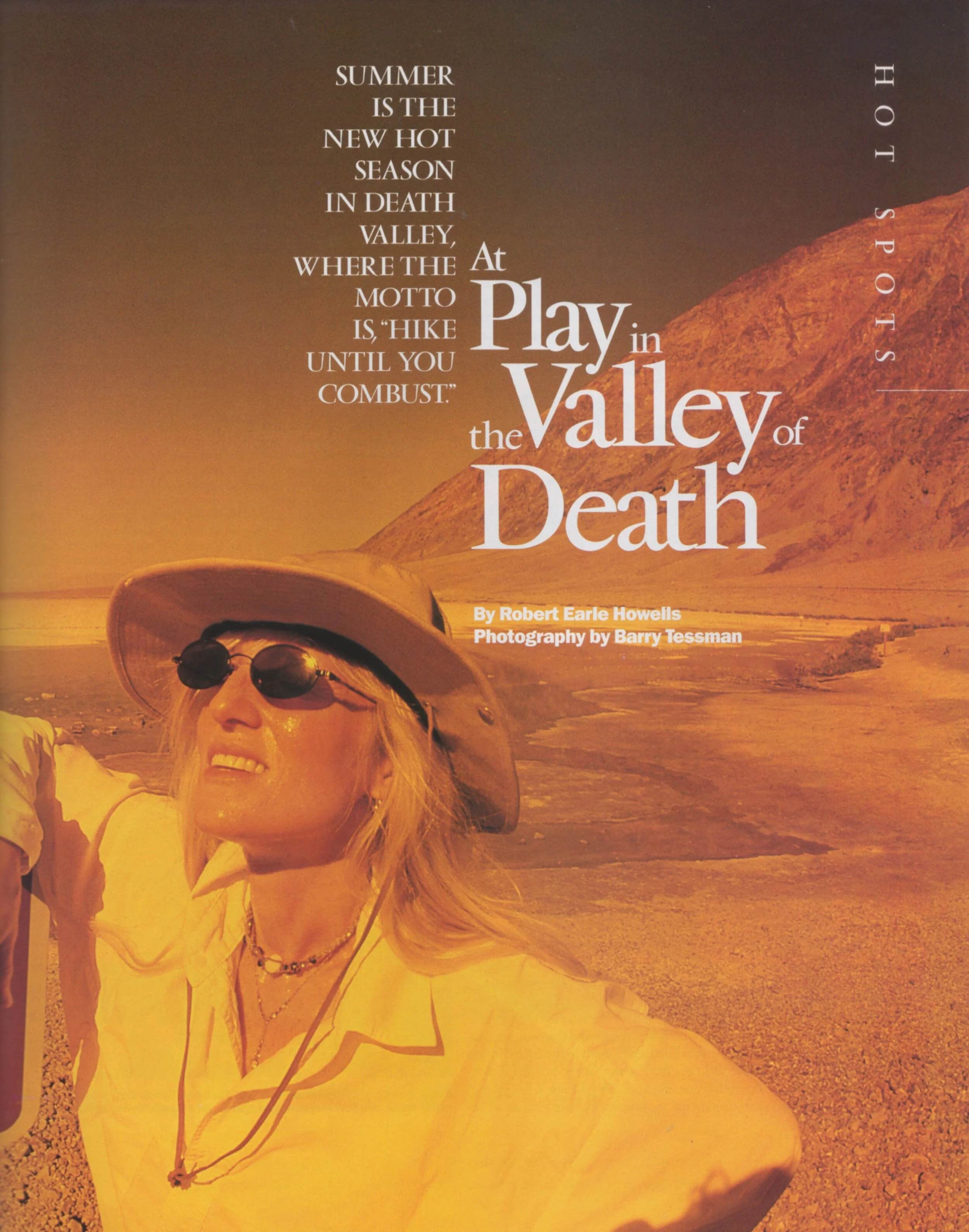

AT PLAY IN THE VALLEY OF DEATH National Geographic Adventure

One of my all-time favorite stories is this feature for National Geographic Adventure for which I timed a visit for the hottest part of the year.

That little bit of audacity solidified a relationship with the National Geographic publications that has lasted 20+ years. Ultimately I ended up writing the Death Valley chapter for Nat Geo’s Guide to the National Parks.

This story has no presence online anymore. Because I’m so fond of it, I’m including the full text here:

IT’S 126 IN THE SHADE, and since I’m not in the shade, I’m the hottest damn fool on the face of the earth. Have to be. It’s the eighth of August, and no one else is walking out into the middle of the lowest, hottest place in Death Valley National Park, which is the lowest, hottest place in the Western Hemisphere. At, of course, the hottest time of day (about 4 p.m.), when the mirror-bright white salt-pan floor of the valley is blasting back a day’s worth of absorbed heat: A 1,000-watt blow-dryer wind whirls up from the floor into my face, the glare maxes out my polarized shades, and I draw steadily on a 90-ounce Camelbak with lifeline urgency, as a diver to a tank of oxygen.

The miserable scenario is weirdly seductive. Simple curiosity, a sort of “let’s watch the tsunami roll in” desire to add to my experiential quiver, had brought me this far. Honest: I hadn’t intended to go any farther. How hot could “hot” get? I’d singe myself briefly and turn back. But I’m finding this alfresco kiln surprisingly alluring. I continue out across this pancake-flat spot called Badwater. I can now barely see through the heat shimmers the tourists back at the roadside turnout making the dutiful pause at the photo-op sign: “BADWATER: ELEV. –282 FT.,” the engines, i.e., air-conditioners, of their Avis-red cars still running. They’re dipping fingers into the eponymous puddle—“yup, tastes bad” and attempting to coax the reluctant, sane member of the party out for a commemorative pose.

I walk about 45 minutes, probably three miles, across the salt. It looks slippery, but the traction is great, the sensation pleasingly like walking across perfect chocolate-chip cookies (crunchy on the outside, soft in the middle)—a three-inch patina of densely packed salt overlays a sea of thick mud (moisture trickles up from an aquifer), so every step yields both crunch and resilience. The only sign of life, sort of, is a windblown omnipresence of desiccated grasshopper hulls. The poor sots had touched down on the frying-pan earth once too often. I’m too infatuated to regard them as any more ominous than anything else here: the jigsaw patterns of the salt crust, or the wind that feels to the eyes like getting too close to a bonfire, or the movie-cliché waves of mirrored heat. High above the tourists on a sheer palisade of the Black Mountains a small sign reads “SEA LEVEL.”

I know extreme heat has a way of causing misfires among those synapses that normally govern common sense. I know that Summer in Death Valley has a ring to it like “winter in North Dakota” or “crawl space in the slimy depths of some bat-dung cavern 500 feet below the earth.” Like any place at any time that anyone sane would avoid. And right now I feel like I’m on the cusp of combustion, like those poor potato bugs I once fried in a convergence of solar rays beneath a magnifying glass. Yet it’s just that intensity that makes summer in death valley so compelling. I’d visited before in fall and late winter, when the air was giddily pleasant. It seemed wrong somehow, a false overlay of Eden on the geography of hell. Really, what’s Death Valley without at least a hint of the possibility of imminent demise? I’m well aware that the air-conditioned sanity of my car is less than an hour away, but for now I’m reveling under a crushing thickness of troposphere and the hyperfocused beams of the hottest sun it’s possible to experience. It’s like holding your breath for a second too long. You won’t die, but you’ll taste the beyond for just a smidgen of a moment and feel the more alive for it.

And hear this: I’m far from alone. My hotel (Furnace Creek Inn) is full. Sixteen foursomes played 18 on Death Valley’s golf course this morning—101 degrees at tee-off, and rising. The visitor center is abuzz with tourists (all asking, according to park ranger Alan Van Valkenburg, the same three questions: “What can we see in one afternoon?” “What can we see without walking too far?” and “How hot is it?”). A digital thermometer behind the information counter answers number three, as it blinks back and forth between Fahrenheit (120s) and Celsius (50s). The metric temp is for the benefit of foreign visitors, which happens to be everyone but me. The Park Service has brochures printed in German, French, Italian, Dutch, Spanish, and Japanese, and they’re all here today, but for the recession-strapped Asians.

Death Valley is on The Circuit. It’s in the guidebooks, the guidebooks must be obeyed, and no 120-degree heat is going to keep the Euros from visiting it. Everyone I speak to has been to Canyon de Chelly, the Grand Canyon, and Las Vegas, and they’re on their way to Sequoia, Yosemite, and San Francisco. The trend began in the early ’90s, when the park concessioner that runs Furnace Creek Inn (lovely, circa-1927, three-diamond, 66 rooms) and Furnace Creek Ranch (the more motel-like spread beside the visitor center, 224 rooms) began shilling their digs in Europe. Then, in 1994, Death Valley scored a coup: It got upgraded from national monument, whatever that is, to national park, which earned it iconigraphic status in the European consciousness, even if the average American missed word of the promotion.

In 1996, the first year that the inn remained open during the summer, guess how many Americans showed up? (Toni Jepson, manager of the inn, put the question to me.) Answer: Zero. None. The odd American does wander in nowadays, but summer visitors to the inn and to the park are still 80 percent Europeans. Most amazingly, summer has overtaken winter and is catching up to spring as the most popular season in Death Valley.

OK, so maybe this has more to do with blind Baedeker obedience than enthusiasm for ogling geology under the world’s fiercest sun (Toni Jepson tells me that virtually no one stays more than one night in summer), but I contend that the Euros are onto something. If Death Valley is fascinating any time, it’s more so when at its most severe. It’s compellingly freakish to walk out before sunrise into near-100-degree heat. Not pleasant, but intensely interesting.

I know this because I’m up before 5 a.m. for a sunrise rendezvous. Ranger Van Valkenburg had tipped me off: Sunrise at Zabriskie Point is an obligatory experience per all the European guidebooks. Sure enough, at least 100 Germans, French, and Italians are milling about the bluffside parking area, wearing tank tops, setting up tripods, speaking in hushed voices. We’re looking westward across the deeply textured folds of a bare-rock badlands, hills of ex-mud left solidified by the recession of a onetime lake that covered Death Valley’s floor. Like most of the rock in Death Valley, the badlands are earth-tonish drab in the flat light, but when the sun finally hits from behind and a hundred cameras click, the lighter rock goes lambent yellow, the darker stuff blares rich reddish brown, and the shadows seem like absolute darkness.

Beautiful, but the appearance of the sun seems a little anticlimactic to the throng, which quickly dissipates. Were they disappointed? I breach the language barrier to ask a couple from Belgium. Not at all, they assure me. It’s just that the guidebook says to move on now to Dante’s View. When I join them (and nearly everyone else) at this higher overlook (it gazes down upon Badwater from 5,475 feet) and later at breakfast, they offer their explanation for Death Valley’s Euro allure.

“It starts with the practical reason that our vacation is in the summer,” says Jean-Louis Baudoin. “But it’s more than that. Nowhere in Europe do we have your vastness or the geographical extremes you have in America and in Death Valley, or the temperature extreme of Death Valley. It’s like your basketball players: They’re 20 feet tall. Your obese people weigh 500 pounds. All this creates a great fascination for us.”

Nonetheless, I’m left to myself after breakfast: The fascinated Belgians move on to Sequoia, and the other Europeans have the good sense to retreat to their rooms, cars, the visitor center, or the very busy general store. Resuming my perverse resolution to do Death Valley by summer, I head out alone, the sun approaching high noon and my Radio Shack thermometer registering 117. (Monitoring the readouts of this high/low, indoor/outdoor jobbie has become an obsession. Last night’s low was 98, and it was barely cooler than that in my room: Even with the AC on full blast and a ceiling fan churning overhead, my room languished in the upper 80s. The highest read is upon an afternoon return to my locked car: 147.)

I’m not totally foolish: I restrict my drives to paved roads and my hikes to a couple of miles. But I seem to have the run of the joint. The lower 48’s largest (3.3 million acres) national park belongs to me.

At Salt Creek, I walk out on a boardwalk to see if I can spot any of the famous Death Valley pupfish, a relict critter about the size of a tadpole that inhabits a few remnant puddles of the long-gone Death Valley lake. It’s a bit worrisome: The little guys are endangered, and most of the creek is dry. I spot nary a pup, but I trust that they’re used to hot summers. They must hole up somewhere. I opt then to exit the boardwalk and head up a broad, sandy wash that cuts through a series of miniature Grand Canyons of dry mud. The footing is good on the crusty sand—not quite sandstone, but a sort of a Moab-in-the-making. I scramble out of the wash onto a plateau to regard a disconcerting sight: My wash is a clone to dozens more, each bordered by the same 20-foot mud cliffs. Wander a few washes away from your route, and you’re certain to die of thirst in a nightmarish labyrinth. Not me, though; I’ve marked each of my junctures with a small rock cairn, and follow my back-bearings to the boardwalk.

Have I mentioned the wind? I contend that there’s some sort of reverse wind-chill thing in effect, that these 20–30 mph winds run up the air temperature to the equivalent of 140 degrees, at least in leaching-of-body-moisture terms. Staying hydrated requires conscious effort: Basically, I drink as much water as my stomach will hold, then squeeze in some more, constantly, the Camelbak hose hovering by my mouth like a pilot’s microphone. The saturation strategy works—the full radiator keeps me from overheating—and I’m able to make a long day of it. I also wander around the ruins of the Harmony Borax Works, where old 20-mule-team wagons doze in the sun. One of the megacarts weighed 36,000 pounds full, and back during Death Valley days, teams hauled them 170 miles—but no, not in summer.

I wrap up my day exploring a slot canyon off a scenic side loop called Artists Drive. Park at the second dip and just walk into the mountain, Ranger Van Valkenburg had told me. I scramble up a low rock face and, like finding the hidden door in a fun house, enter a passage that penetrates the face of the Black Mountains. For the next half hour I continue up a series of scrambles into progressively narrower chambers until the defile is barely 15 feet across, but 150 feet deep. Finally I reach a pitch that’s about 30 feet high, but this one’s pretty sheer—an easy 5.5 if I’m roped, but I’m not—it’s nigh on to sunset, I’m alone…I turn back.

Death Valley does have a few logical places to hang in summer, and I decide to spend most of the next day in the visitor center and in the Furnace Creek Inn pool. Toni Jepson tells me that she’s never seen anyone sunburned in Death Valley, and I understand why. The tile-lined pool is lovely, and constantly replenished with fresh water—no need for chlorine here—that burbles out from nearby Travertine Spring at 82 degrees, washes through the pool (and warms to 90-something), and then flows out again to water the golf course. The womb-temp water’s too warm to swim in for long. And once I’m out, any evaporative-cooling effect lasts five seconds. Then it’s too hot to linger.

It’s much cooler inside the VC, where I’m talking summer lore with Alan Van Valkenburg, on break from telling foreign tourists how hot it is. The events that earned Death Valley its name—a party of wayward ’49ers, stranded, starving, but eventually rescued, uttered, “Goodbye, Death Valley” as they left—unfolded during the gentler months of December and January. In July 1996, a German family wandered onto a rugged side road in the Butte Valley (southern) area of the park in their rental car, then clattered up a closed road. The car, with three flat tires, was spotted by a plane in October. No trace of the Germans. Generally, though, summer in Death Valley is fairly self-regulating—witness the lack of sunburn. There’s the odd case of heat exhaustion and plenty of car breakdowns, but it’s just too darn hot to invite much in the way of bone-bleaching adventure.

And why is it so hot? The sub-sea-level valley is so low, and its framing mountains so high (the Amaragosa Range to the east is in the high 5,000s, and the Panamints to the west top out at Telescope Peak, 11,049 feet) that summer heat has nowhere to go. Some hapless summer campers bank on cooler nights, but any dip below 90 occurs only just before sunrise. (The Furnace Creek campground is empty during my visit.) Death Valley has long claimed the Western Hemisphere record high of 134 degrees (it supposedly hit 136 somewhere in Libya once), and made news again last summer when it reached 129 on July 17. Figure it’s 200 degrees on the ground those days.

Which reminds me: The answer to the question you’ve forgotten to ask. Sure it’s hot, Bob, but can you fry an egg on the ground? Sadly, no. My pat of butter melts quickly, but the egg just sits there, not even managing a mediocre over-easy.

For my last evening in Death Valley I heed another Van Valkenburg tip. If you’re going to see wildlife anywhere, it’s in the sand dunes at night—and tonight’s a full moon. Sidewinders, kit foxes, coyotes, kangaroo rats—it should be a fair moonlight frolic. This experience is obviously not in the European guidebooks. It’s just me under the heavenly klieg light, and I walk a mile or so up and down 60- and 70-foot rises until I claim a perfect sky box. If you ever just want to do a little cogitating, or join Gaia in rapturous union, or just be way, way far alone, this is the place and the time. You probably won’t be distracted by any kit foxes or sidewinders. You won’t be distracted by anything. You’ll see the world’s brightest moon and a lot of sand, and it’ll be 100-ish, and you’ll probably be the hottest damn fool on the dark side of the earth.

SEARCHING FOR BIGFOOT Westways

I love a good quirky story, especially when it sends me up to gorgeous wild country in Northern California. Home of Bigfoot.

Some readers were offended that Westways devoted perfectly good magazine space to covering a story about a “mythical” creature. Ha! Those readers have never walked in Bigfoot’s prodigious footsteps. I have.

Excerpt:

It’s only 59 seconds of 16mm film, but those 954 frames are among history’s most-studied strips. In 1967, Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin, two rodeo cowboys from Oregon, horse-packed into the Bluff Creek drainage about 50 miles north of Willow Creek, in Northern California. While there, they filmed a shaggy giant as it walked up the hillside away from them. Some say the film depicts a guy in an ape suit. Others contend it’s footage of Bigfoot. No question which theory is more intriguing.

I wanted to meet this ambassador from an era when the world was wild, and huge, hairy humanoid creatures were plentiful. Every locale has its resident numen, a spirit or a quality that represents the essence of the place—a mystery that hovers over the loveliest landscapes. Or strides through it, with very large feet.

THE BEST SPORT SUNGLASSES Wirecutter (NY Times)

I have an enduring fondness for great outdoor gear, a passion that served me well as the cofounding editor of the Outside Buyer’s Guide, published annually by Outside Magazine—a job I did for eight years.

I don’t do a lot of gear writing anymore, but when the opportunity came up to write for Wirecutter, the highly respected gear-review site published by the New York Times, I jumped at it. This one focuses on sport sunglasses. I love that Wirecutter allows a deep dive into all of the products it covers. Prepare to dive deep.

Excerpt:

If you like to play outside during daylight hours, you should wear sports sunglasses to protect your eyes from foreign objects and ultraviolet radiation. After cycling, trail running, hiking, or snowshoeing daily over the course of two months, constantly swapping out 40 models of sunglasses, we believe that the Ryders Seventh Photochromic represents the best choice for eye protection in a wide range of activities, and at a good price.

READ THE FULL REVIEW

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC GUIDE TO NATIONAL PARKS Contributing Author

I’ve always been a huge fan of our country’s best idea, the national parks, and have written dozens of features and packages on the parks. For many years I penned National Geographic Adventure’s annual national parks package, which caught the attention of the National Geographic book division. I’ve contributed to a number of books for Nat Geo, including their signature guide to the national parks, for which I wrote the Death Valley and Joshua Tree chapters.

Excerpt:

Death Valley is geology laid bare—a scarred, gashed, desiccated place where striated canyons gouge forbidden-seeming mountains, and where a vast salt-pan floor shimmers under a fierce sun. Ferocity reigns here. Nothing seems familiar. Yet for all that, Death Valley’s 300-plus miles of paved roads and a smattering of oasis-style facilities make it surprisingly easy to visit, while not diminishing at all the park’s overpowering impact.

AMAZON RAINFOREST DOCUMENTARY Outside Television

My article for Outside magazine titled “The Teachings of Gerineldo Moises Chavez, or, The Rainforest Is a Great Place to Save, But I Wouldn’t Want to Live There” was so wildly popular (and won a Lowell Thomas Gold Award for Best Adventure Travel Story) that Outside commissioned me to reexperience that Amazon survival adventure for Outside Television. I wrote the script, and I guess you could say I starred in it, though the true star was my gifted and patient guide, Moises Chavez.

The result was every bit as successful as the article, and won a silver Teddy Award in competition for the year’s best conservation film.

Major credit goes to director Melissa Forman and to executive producer and prolific filmmaker Les Guthman, who hosts the film on his XPLR Productions Vimeo channel.

WATCH THE SHOW

REVISITING THEODORE ROOSEVELT National Geographic

In light of current events, National Geographic asked me to virtually revisit Theodore Roosevelt National Park, which I wrote about for National Geographic Traveler several years ago.

For this new story, I gathered Native American, Black, and National Park Service perspectives, and spoke to the author of a new book on Theodore Roosevelt’s conservation legacy.

I’ve always greatly admired Theodore Roosevelt. But as I explain in the article, he was a complex man who held some troubling views.

An excerpt:

It’s easy to become enthralled with the 26th president of the United States, particularly if you love the outdoors he helped preserve. So several years ago, when I visited North Dakota’s Theodore Roosevelt National Park to research a story for National Geographic Traveler, I couldn’t help but fall under his spell, just as I was enamored by the landscape he cherished.

Then, in June of this year, Roosevelt found himself suddenly under scrutiny. The precipitating event was the decision by the American Museum of Natural History in New York to remove a bronze statue of Roosevelt, which depicted him on horseback, towering above a Native American and an African man. The statue, unveiled in 1940, was undoubtedly racist. Even Roosevelt’s great-grandson agreed it should be taken down.

The statue was commissioned decades after Roosevelt’s death; he, of course, had nothing to do with it. But the questions arose, and they were good questions. The statue was racist. What about the man?

READ THE ARTICLE

FISHING WITH UNCLE ORV Avenues Magazine

I’m proud of this essay for many reasons, but mainly because it memorializes two men I loved and admired: my father, Major Billy W. Howells, and his younger brother, Col. Orville J. Howells Jr. The article was published a month before my father died.

It has no life online other than here, so I’m including the text in full:

The two old geezers on the creaky dock look about like any other ill-chapeaued fishermen beginning a day of bass fishing at Lake Cachuma—except that most of the other geezers are already out on the lake. These two are hunched over the hind end of an undistinguished looking boat, unwrapping about 100 yards of fishing line from the propeller of an Evinrude.

Once the prop is liberated from its filament snare, the geezers set about starting the engine, a process that entails a thorough dockside dismantling of the powerplant’s viscera— a complete engine rebuild, apparently, that is to no avail. At last, a brainstorm. New spark plugs. She purrs like a kitten, and at the crack of noon, Cachuma’s most fearsome bass anglers are on the prowl.

The fishermen happen to be my father and his brother—Billy and Orv—and they have been fishing together for more than 60 action-packed years, and they do occasionally catch fish. Their craft is Uncle Orv’s ominously monickered What Now?, a vessel that seems to have seen better days. Ask about those better days and you get stories. You soon understand how the boat got its name. And why, despite a parade of plagues every time they go fishing, these two men in their 70s tolerate each other’s company every chance they get.

Every once in awhile they graciously tolerate my company, too. This trip to Cachuma is an anniversary of sorts. It was 25 years ago, we think, that Uncle Orv parked his camper over the decaying corpse of some flattened fauna that maliciously time-released noxious pheromones in the wee-smalls of a subsequently sleepless night. And when Uncle Orv the next morning thwarted a thick fog by dead-reckoning our way to a favorite cove—only it turned out that we’d spent a half-hour making a giant loop around the lake right back to the dock. It’s not unusual to get a late start when you’re fishing with Uncle Orv.

This day Uncle Orv steers us more directly to his latest can’t-miss cove, near the site of the release of 500-plus bass caught in a tournament the week before. A sure thing. The banter, laconically interspersed among all the lure-choosing and rigging and careful sixth-sense preparations of big-bass anglers, goes like this:

Dad: “So it’s bass first?”

Orv: “You’re the decision-maker, Intrepid Angler. I’s mere the guide.”

Dad: “No beer till we catch the first fish.”

Orv: “That’ll make for a long, dry day, Bub.”

It indeed appears that way, so after awhile, I violate Prohibition, pass around some Red Dogs, and fish for stories . . .

There was the time Uncle Orv tossed a live net brimming with a nifty mess o’ trout over the gunwale of the What Now?. Problem was, said net was unaffixed to said gunwale, and the incarcerated fish headed for Davy Jones’s locker. Uncle Orv heroically dived overboard and discovered “water gets dark at 20 feet.” A humanitarian effort?

Orv: “Sure was! To keep him from killing me.”

Dad: “Because I caught most of those fish.”

Orv: “O-ho! Now hear this!”

There was the time Uncle Orv snagged Dad’s cap on a backcast and neatly tossed it 30 feet in the lake. “Fortunately, my head stayed intact.” Judging by the weird one he’s wearing today—one of those mesh-and-foam jobs that says something clever like “Watch Out Trout” on it, the cap deserved the dunking.

There was the time when a monstrous rainstorm pelted the What Now? ashore. Uncle Orv had dutifully affixed its water-resistant (hint: key word is resistant ) cover and “I assumed all was well . . . until I looked out and saw both tires flat.” It seems that the weight of a boat full of water (why bother to open the drain plug when the boat is covered?) is too much for trailer tires to bear. He peeled back the cover to find a full tacklebox under water. Both batteries under water. A very late start to that fishing day.

There was the What Now?’’s maiden voyage, when she was planing so smoothly across the glassine surface of Lake Nacimiento until Uncle Orv inexplicably backed off the throttle and promptly thwacked a submerged rock. It just took a little fiberglass Band-Aiding to get her under way again. But the story has a happy upshot: The brothers had stopped en route to the lake that day at my great uncle’s insurance office to take out a policy on the boat. Amid fully expected accusations of fraud, Uncle Orv filed his first claim on the effective date of the policy.

The unraveling of these stories means that our fishing day is thus far unsullied by the presence of bass. Dad breaks the streak, sort of, by announcing a hit. To which Uncle Orv responds, “We’ve never been successful frying hits, Bub. It’s like boiling up a mess of deer tracks.” A strand of moss on Dad’s lure dispels the hit theory, and our guide deems it time to move on: “What say, Boy-San, we try two more protected coves, then troll the bounding main, after which it will be declared sandwich-and-brew time.”

About this time I ingenuously ask where bass like to hang out, which draws guffaws as the dumb question of the day.

We arrive at the next can’t-miss cove and the anglers rig up.

Dad: “What manner of gifilligous ding are you putting on there?

Uncle Orv: “A brand-new single-fin wombat. I’m testing my theory (alluding to the What Now? ’s recent drenching) that bass are offended by rusty hooks.”

Dad: “When all else fails, I say put on old Fat Wrap.”

Uncle Orv: “All has failed. I wore out old Fat Wrap in the first cove.”

After another fruitless while, Dad switches to a Hula Popper, which looks something like the bad ceramics you see at sidewalk art shows. Bass apparently like bad ceramics—this one looks like a tropical fish with its pink mouth wide open—just as they like cheap rubber worms of the sort you used to scare girls with.

Uncle Orv sagely disputes Dad’s selection: “Not a top-water lure. Not this time of year.” A few minutes later, Dad reels in the first bass of the day, and, to his credit, unsmugly so. But there seem to be grave doubts as to the legality of the catch on the part of the non-catching party. It’s Dad’s triumph, though: “Basso profundo” tips the scale at 12 ounces. A keeper.

Few of the fish’s brethren in this cove succumb to the temptation of bad ceramics, so we proceed to troll the bounding main “for anything stupid enough to get in our way.” I note an irony of high technology: The sonar device that Uncle Orv uses to scout out schools of fish beeps periodically with an urgency both men seem to ignore. Finally, I ask why. Uncle Orv chuckles: “ Because we can’t hear the dang thing!”

Dad chimes in with a recollection of their boyhood days fishing the Mississippi River in Iowa: “We caught more fish with cane poles and bobbers than we have ever since.”

It is during these segues, with the motor droning just loud enough to quash conversation, that I can see the Air Force pilots in the faces of my father and uncle. Both were career aviators—transports, bombers, fighters. Three wars. And I see an identical fixed gaze in the piercing eyes of the brothers as we motor across the lake, as if they see something I don’t, or they’re looking for something I wouldn’t expect to see.

I theorize that the mellowing of both men, so evident on this weekend outing, may have something to do with the temporal distance between them and the wars they fought—memories I can’t imagine, replaced by fishing memories, where the consequences of misadventure are nothing but some lost fish or a late start; where responsibilities have nothing to do with life and death.

It’s as if Uncle Orv senses my reverie. “There’s a parallel between fishing and flying,” he announces. “They say flying is hours and hours of boredom with moments of sheer terror. Fishing is hours and hours of boredom with moments of sheer pleasure.”

Dad waxes a little philosophical: “But there’s a lot of pleasure in the boredom, too.”

Uncle Orv: “Oh, yeah. You can’t catch fish in the living room. Beats watching the darn tube. That’s what makes young people old and keeps us oldsters young.”

What now? For the last hour we’d been tacitly assessing a gathering of silver-black clouds to the west. They’re upon us now, and we’re getting pelted with the first drops. Dad assumes the role of squadron commander and orders a 180 back to base. Sandwich-and-brew time will take place ashore. By the time we get there, we’re soaked, cold, and laughing. This time, we agree, we’ll cover the boat and remember to open the drain plug. After all, we’re going fishing with Uncle Orv again tomorrow.